Posted: March 1, 2022

Get a Soil Test to Determine if Your Soil is Ready.

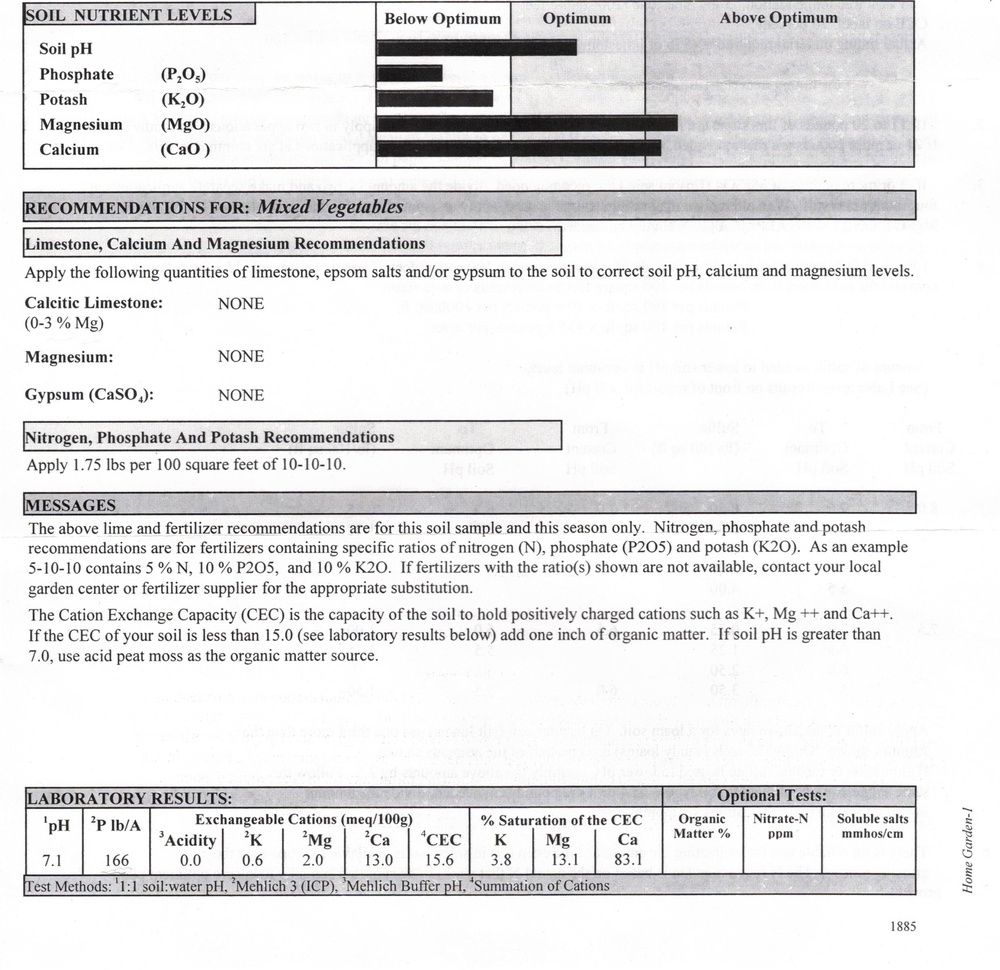

This is the author's soil test result. Note the instructions provided for amending the soil.

The ground is thawing, the days are getting longer, and I'm getting itchy to get into the dirt again. As a long time gardener, I have a list of spring chores waiting for me. Even a new gardener, or one with a season or two behind her, has spring chores to look forward to. Where to start?

Where do gardens start? The soil, of course. The soil is the basis of any garden; it provides the nutrient-rich environment that feeds the plants. Healthy soil supports healthy plants, whether we grow them for food, blooms, beauty, or more. Soil scientists tell us that soil is more than a medium to supply nutrients to roots and a home for earthworms. Soil is an ecosystem, a community of many types of organisms that interact with minerals, air, and water. Gardeners realize that caring for the soil includes caring for the life abiding in the soil.

When you turn over that first shovelful in the spring, a wonderful earthy aroma tells you that the soil is alive with microorganisms. We can also see how things look. Visually, we notice the mineral portion, the portion derived from rock that disintegrated over millennia from the material making up the earth's crust. It varies from place to place, depending on the geological forces that put the material there over time. It also means the minerals present will vary depending on location, too.

If you have gardened for a while, your soil likely includes organic matter -- decaying bits of leaf litter, grass clippings, or compost. There is also organic matter you can't see -- very tiny bits of mostly digested organic material -- left behind by the worms and insects which made the soil tunnels you see. You don't see them, but soil is also inhabited by the microscopic creatures of the ecosystem -- fungi, bacteria, etc. These all make up the living portion of healthy soil, and we want to do our best to keep them happy since they are important to the health of our plants.

You know the plants you are nurturing need soil minerals. What do they need? How do you know what is already in your soil? The best way to find out is with a soil test, which Penn State can provide. Once you've purchased a soil test for $9 from the Penn State Extension Office (670 Old Harrisburg Rd., Gettysburg), you obtain soil from the area you want to test -- your vegetable garden, lawn, flower bed, or any area you want to test. Each test result tells you what is necessary to supply the correct amount of nutrients important for plant growth and provides instructions for adding the correct amount of deficient material for that particular garden. And yes, each garden has different nutrient requirements, so each one needs a separate test.

The soil test tells you whether the amount of phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium, and pH is insufficient, optimal, or higher than optimal. If your garden is deficient in any of these nutrients, you are given the amount of soil amendments needed for 100 square foot of garden to bring your soil up to snuff.

If you have read about gardening, watched television shows or youtube videos, or listened to Zoom lectures (Penn State Extension offers these, too!), you probably heard that one of the principal nutrients your garden needs is nitrogen, but it isn't listed on the soil test form. Instead, they instruct you to add nitrogen based on the amount of phosphorus you need. That's because nitrogen exists in the soil in multiple chemical forms and soil microbes change it between those forms as they go about their daily activities. Nitrogen needs are often similar to the amount of phosphorus needed; that is why the instructions link the two. However, that is not the case for lawns, which needs much more nitrogen than phosphorus.

PH is important because it determines how well plants can access the other soil minerals. If your soil's pH isn't optimum, there are instructions for fixing that, too. If your soil is too acid, it tells you how much lime per 100 square feet is needed to neutralize it. Or if it isn't acid enough, the results will tell you how much gypsum, or 'sulfur,' to add to lower pH.

The test results also list a category called cation exchange capacity, or CEC. Fortunately, they also tell you whether it's something you need or not, and how much organic matter to add if you need it, without trying to tell you what it technically means to a soil scientist.

To get a good soil sample, follow the instructions provided with the soil test. Regardless of the type of garden you are testing, dig about 6 inches into the ground, grab a sample, and put it in a container. Do this for ten samples in ten random spots, and mix all the samples thoroughly. Be sure to remove large bits of organic matter and pebbles. I allow the sample to dry for several days because the cost of mailing the sample is the responsibility of the gardener and moist soil is heavier than dry soil. Put about one 8 oz. cup of soil into the pouch provided. Be sure to fill out the proper form, indicating what kind of garden or lawn you are testing. After you put the soil and form in the mailer provided, seal it and take it to the post office for shipping.

When you get the results, you can make any necessary adjustments. If you find yourself befuddled by the results, help is available. Master Gardeners can answer your questions and the Hot Line is now available through the winter from 10 am to 2 pm on Wednesdays, returning to Monday, Wednesday, and Friday after April 1.

Now, go outside, take a deep breath, and welcome spring. It's time to get our hands dirty again.

Debby Luquette is a Penn State Master Gardener from Adams County. The Penn State Cooperative Extension of Adams County is located at 670 Old Harrisburg Road, Suite 204, Gettysburg, phone 717-334-6271.